Spotlight on Racism in Medicine during a Pandemic – We have the Solutions

On December 20 Dr. Susan Moore, a Black physician specializing in Family Medicine and Geriatrics, died from complications of Covid-19. Dr. Moore’s story is well known because it was posted on Facebook and viewed thousands of times. She videotaped herself in her hospital bed testifying to the mistreatment she was experiencing and stating that ‘If I was white, I wouldn’t have to go through that.’ Dr. Moore was discharged from that hospital on December 7th and readmitted to another hospital 12 hours later with a spiking fever and dropping blood pressure. She is not the only Black person in 2020 to post their report of mistreatment on social media and die soon after. During the last two trimesters of her pregnancy, graduate student Amber Rose Isaac’s concerns were not heard by her doctors in telemedicine visits, and they would not see her in-person. Amber was at risk for complications due to an abnormality in her blood, detected in February, but not addressed. On April 17 Amber tweeted her frustration in dealing with ‘incompetent doctors’ for two trimesters. She died 4 days later during the birth of her son.

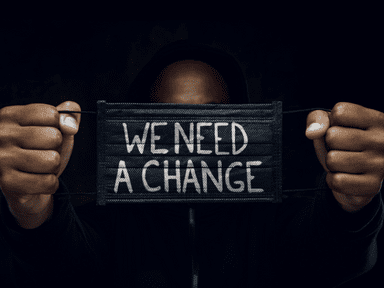

Since the killing of George Floyd, viral videos of verbal and physical attacks on people of color by white people – on the streets, in coffee shops, parks, and classrooms – have made racism in our society plainly visible to many of those who were previously in denial. Whether perpetrated by police, or private citizens, or those in the ‘helping’ professions, racial discrimination is coming under a spotlight. The exposure has not stopped the attacks, however. Reversing 400 years of white supremacist indoctrination will take much more than giving media attention to the devaluation of Black lives.

Now the spotlight is shining on racism in the medical-industrial complex. There are the videos and tweets. There are the news stories about the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on Black and Brown and Native people. There are the proclamations by departments of health and medical professional organizations that racism is a public health emergency. Unfortunately, none of these alarms are likely to change the racially biased behavior at the patient’s bedside, or racism in medical education and research, and in the delivery of medical and maternity services. Black researchers, midwives, doctors, and doulas have solutions. Shining a spotlight on them may increase the chances of substantive and meaningful change. Here are just a few of many promising maternal health initiatives to amplify Black mother’s voices and improve their care.

SACRED Birth in the time of Covid-19, the first of its kind, is a Black women-led quality improvement research study, designed for and with Black mothers and birthing people who share their patient experiences of care in hospital settings during labor, birth, and postpartum in six key areas: Safety, Autonomy, Communication, Racism, Empathy, and Dignity. Led by Karen A. Scott, MD, MPH, FACOG, Associate Professor and Applied Epidemiologist at the University of California San Francisco, SACRED Birth aims to validate the first-ever Patient Reported Experience Measure of OBstetric racism©, also known as the PREM-OB Scale™. ‘The information gained from this novel survey instrument will help hospitals, health plans, scientists, funders, and the public better understand how racism and other forms of discrimination and neglect affect the way hospitals provide care, services, and support to Black mothers and birthing people during labor, birth, and postpartum.

The National Perinatal Task Force (NPTF) is a consortium of community-based health centers or organizations who have committed to offering respectful, compassionate, and person-centered maternity care. Founded by Midwife Jennie Joseph of Orlando, Florida, NPTF is a grassroots movement of Perinatal Safe Spots (PSS) in areas where it is not safe or conducive to being pregnant or parenting young children. Each PSS is a resource for pregnant and postpartum people to get the physical, emotional, and informational support they need for their family’s health and wellbeing.

Midwife Jennie Joseph has shown how supportive and easy access prenatal care, the JJ Way, can eliminate racial disparities in prematurity and low birthweight. In 2020 she established Commonsense Childbirth School of Midwifery, the first Black owned and nationally accredited school of midwifery in the US. Eliminating racism will require increasing diversity in the maternity care workforce.

According to Dr. Lucian Leape, physician and professor at Harvard’s School of Public Health, ‘Disrespect is a threat to patient safety because it inhibits cooperation essential for teamwork, cuts off communication, and is devastating for patients.’ Countering the medical culture of disrespect, Black Coalition for Safe Motherhood promotes healthcare advocacy of birthing people. Â Participants in community workshops practice what to say and who to speak to when they are being rushed, disrespected, or dismissed as they seek help in medical settings. In so doing they assert their rights to respectful care, amplify their voices, and push back against racism in medicine.

These are just a few of the solutions developed by Black women with very limited resources compared to those of the medical-industrial complex, which gets 23% of it’s Medicaid income from maternity services and has the worst maternal mortality rates among wealthy nations. While in the US profit is prioritized over the health of mothers and babies, the Black community is leading the charge for respect, equity and quality improvement in maternity care.